Lights, camera, organ! On Sun, Feb 16 at 3:00 pm, esteemed organist Aaron David Miller will add the pipes to one zany character’s dream. Witness the phenomenon as Miller crafts a soundtrack to Buster Keaton’s iconic film The Cameraman in real time. Discover the rich history behind this blend of silent cinema and live soundscapes.

Aaron David Miller improvising music for the silent film The Phantom of the Opera. Photo © Tony Nelson Photography.

Putting the “Pro” in “Improv”

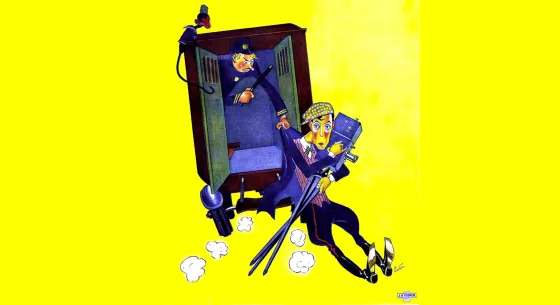

Buster Keaton in The Goat (1921). Film still from Metro Pictures, 1921. Joseph M. Schenck, producer, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“The Great Stone Face"

Buster Keaton and Josephine the monkey in The Cameraman. Still image from public domain.

Going Out With a (Silent) Bang!

Edison projecting kinetoscope, an early motion picture exhibition device. Photo by NPGallery, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Behind the Camera

An inside look at some of the Northrop organ pipes, including some as small as a pencil. Photo © Patrick O'Leary.